As Airways Magazine writes, the first passenger flight of the Airbus A380 was a momentous occasion. Singapore Airlines, the aircraft’s launch customer, set up a display at Singapore Changi Airport, noting that the October 25, 2007 flight was going to be the first commercial flight in the world for the new plane. Passengers, as Airways Magazine wrote, had to bid for seats on the aircraft, with proceeds going to charity. Passengers for the flight arrived in the early morning hours. Eventually, Singapore Airlines CEO Chew Choon Seng cut a yellow ribbon, beginning boarding for the first A380 flight. At 8:15 local time, Flight SQ380 rotated towards the skies and into the history books.

A Look Back

As Airways Magazine notes, European aircraft manufacturers in the 1960s wanted to compete with America’s manufacturers with innovative aircraft. But there was a problem. America’s Boeing, McDonnell Douglas, and Lockheed were powerhouses that enjoyed strong sales from the popular American air transport market. European manufacturers had novel designs, but not the production to go up to bat against America’s manufacturers. Eventually, some European aircraft builders came to the conclusion that to compete with the Americans, they needed to collaborate. In 1970, Airbus Industrie GIE was formed as a consortium of European aircraft manufacturers. Initial shareholders were France’s Aérospatiale and West Germany’s Deutsche Airbus. The UK’s Hawker Siddeley joined in, as did Dutch Fokker-VFW and in 1971, Spanish CASA purchased some shares in the venture. The first aircraft to come out of this consortium was the Airbus A300 in 1972, a plane that started development in a European multinational collaboration before the formation of Airbus Industrie. Airbus entered into a hot time for commercial aviation. As Simple Flying notes, McDonnell Douglas and Lockheed locked into a battle of trijets with their DC-10 and L-1011 TriStar, respectively. Meanwhile, Boeing was seeing some incredible success with its 747 jumbo. The 747 became such a famous aircraft that to this day, people call it the “Queen of the Skies.” And it was more than just its form, as the 747’s seating capacity allowed for lower airfares, which meant more people were able to fly. Airbus engineers took note, and dreams for what would become the A380 began materializing as early as 1988. That year, as told by the book Airbus A380: Superjumbo of the 21st Century, Airbus engineers gathered around a table to study sketches for a plane that seemed like it would never get built. Those sketches were for an aircraft capable of carrying more than 800 passengers, more than the maximum of 660 that the 747-400 of the era was designed to carry in a single seating configuration. Only this team, a part of Airbus’ New Product Development and Technology department, knew of the idea. Not even Airbus leadership was aware of it. As the book continues, Jean Roeder, engineer of the wing concept for the A330 and A340, noted that Airbus wanted to capture 30 percent of the market. Roeder felt that if Airbus was going to meet that goal, it needed a set of aircraft like Boeing and the 747’s monopoly had to come to an end. As the book notes, the end of the Cold War was in sight at the time, and airlines and aircraft manufacturers both saw the potential for spikes in air travel. At the same time, air travel was already increasing in regions like Asia. More and more planes were taking off and landing at major Asian airports to meet the increasing demand. There was a fear that airports would be congested with the number of planes required to meet demand.

Solving Airport Congestion

What’s a way to reduce airport congestion? Instead of sending passengers off in multiple planes, corral them into a single, massive plane. At the time, the hub and spoke model was the norm. In this model, there are central “hub” airports and smaller “spoke” airports. In this model, you fly from one airport to a hub airport to catch a plane to another airport. Simple Flying further explains how the model works: Elaborating further, a point to point model means flying from one point to another, rather than forcing travelers to go to a hub to ultimately end up at their destination. But because the point to point model means perhaps flying between two small airports, it can mean fewer passengers per plane. The hub and spoke model allows airlines to optimize routes by packing planes full of people, something that aircraft like the 747 are great for. Many international airlines have a single hub airport – the Gulf airlines, Singapore Airlines, and Cathay Pacific are good examples. In each case, the vast majority of their flights either arrive or depart from their hub. If you want to fly from Los Angeles to Laos on Singapore Airlines, you will connect in Singapore. If you’re going to fly from Auckland to Athens on Emirates, you will change planes in Dubai.

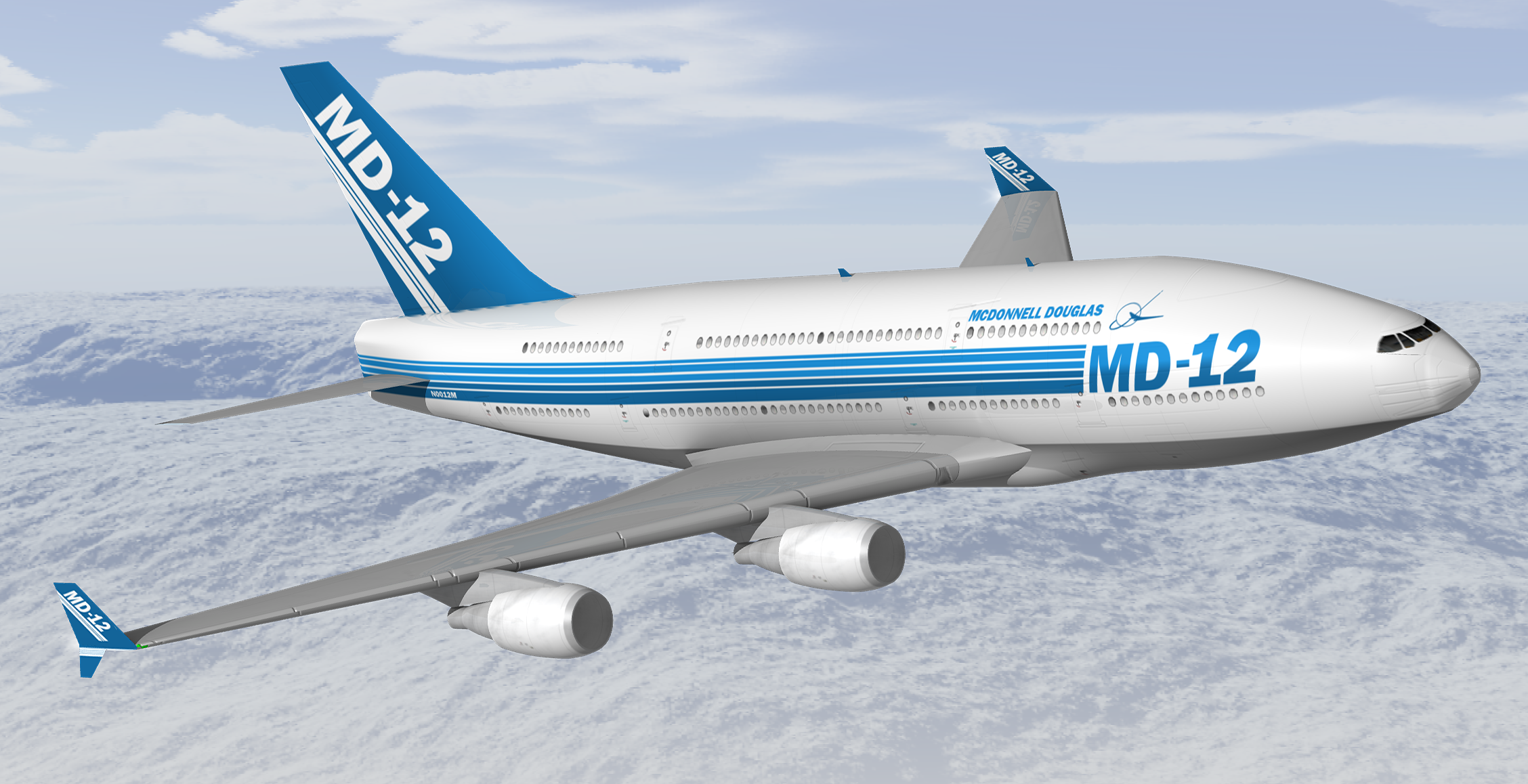

Manufacturers Pitch Double Decker Aircraft

Airbus looked at different ways to take on the 747. One configuration was two A340 fuselages placed next to each other, and another was a flying wing idea. Airbus eventually settled on a double decker. The aircraft maker wasn’t alone in the idea of going even bigger, as Lockheed was looking into the future of very large commercial airliners. Boeing also considered a larger aircraft with a full-length upper deck, but abandoned the idea for more variants of the 747. Over at McDonnell Douglas, the concept for the double-decker MD-12 was taking shape. McDonnell Douglas pitched the aircraft to the airlines, and scrapped the idea when it didn’t find any bites. McDonnell Douglas itself would later get absorbed into Boeing.

Development And Production

But Airbus moved forward with its A3XX, targeting 15 percent lower operating costs than the 747. In 2000, Airbus estimated that 9.5 billion Euros were needed to complete the aircraft, half of which would come from Airbus. It projected that the plane, now named the A380, would recoup those costs by 2010, and generate 40 billion Euros after. The plane’s name was also a departure from Airbus norm, where planes were numbered sequentially from 300 to 340 at the time. The “8” represented not just what the aircraft’s cross section looked like, but was considered to be a lucky number in the Asian markets that Airbus targeted. Production of the A380 involved structural sections of the aircraft being built in France, Germany, Spain, and the UK. And those parts would be delivered to Toulouse, France for final assembly in interesting ways. Components often found themselves on barges or onboard the famous A300-600ST Beluga. An entire water and road route, the Itinéraire à Grand Gabarit, was built to facilitate the movement of A380 parts to the Toulouse final assembly. If you were lucky, you might have seen a ship sail by with “Airbus A380 On Board” painted along the side. Or perhaps you’ve seen parts rolling down the road on the way to the factory. The first Airbus A380, registration F-WWOW, made its first flight on April 27, 2005. In March 2006, evacuation tests were performed, where 853 passengers and 20 crew were able to exit a darkened A380 with 16 random exits blocked in just 78 seconds. And after three production delays totaling over a year, deliveries finally began in 2007, with Singapore Airlines flight SQ380 taking off towards Sydney that October. There’s no doubt that the Airbus A380 is a technical marvel. The aircraft is certified to fly with a maximum of 853 seats when configured as all-coach, though a typical seating arrangement is 550 seats. It’s 238 feet, 7 inches long with a wingspan of 261 feet, 8 inches. It weighs in at about 628,317 pounds empty and can take off loaded to 1,267,658 pounds. Everything about this plane is huge, including its 85,472-gallon fuel capacity. Airbus A380s are paired with either Engine Alliance GP7200 or Rolls-Royce Trent 900 turbofans, which combined with the fuel load provide about 8,000 nautical miles of range.

A Big Plane With Big Fans And A Big Problem

Passengers and aviation geeks alike marvel at the A380, and there are plenty of rave reviews of flying on these graceful birds. Reading reviews of flights, even outside of First Class, you’ll encounter words like “glamorous,” “comfortable,” and “incredible.” By all accounts, it seems passengers absolutely adore these planes. Pilots seem to enjoy them too, with one pilot going as far as to call the giant nimble. Though, experiences from other members of the flight crew reportedly vary depending on airline. It’s absolutely a dream of mine to fly on one of these before they’re out of the sky. Sadly, the fanfare over the new aircraft didn’t translate to sales. Major hub and spoke operators like Emirates and Singapore Airlines liked the aircraft, and Emirates eventually became the largest customer, operating 123 of the total 251 customer A380s produced. Lufthansa got 14 A380s, while British Airways got 12 and Qantas also got 12. In total, 14 airlines placed orders for the giant, but the biggest by far was Emirates. The A380 presented problems for other airlines and some airports. The International Civil Aviation Organization classifies the Airbus A380 as a Code F aircraft for its massive size. Some airports simply lack the infrastructure to support such a large aircraft, and as Simply Flying notes, those airports needed to modify their infrastructure. This included enlarged taxiways, enlarged gates, and modifications to lighting and signage. Airbus says that some 140 airports could support scheduled A380 service, and 400 airports could serve as diversion airports. For the airlines, the hard part was that to profitably operate a plane of this size, you had to fill the seats. For years, smaller more efficient planes have been allowing point to point routes to be popular and profitable. These routes tend to use smaller planes with fewer people on board. This was a model that Boeing designed the 777 for. Or said another way, as Reuters notes, the A380 was designed for a dying model. Airbus didn’t even find a single U.S. customer for the aircraft. Making matters worse was the pandemic, which reduced passenger air traffic so much that many A380s were retired from service early. Even Emirates, the airline that the aircraft worked the best for, retired its first A380 in 2019, and had five retired by June 2021. Singapore Airlines scrapped the A380 that made the type’s first commercial flight in 2018; the plane was barely over a decade old. Still worse is that, as Forbes writes, the fear of airport congestion forcing airlines to fly once-daily flights on huge planes never materialized. At one point, Emirates was the only customer keeping the A380 alive. But, in 2019 the airline canceled an order for 39 A380s, replacing them with an order for 40 A330-900s and 30 A350-900s. Airbus saw the writing on the wall and announced that it would end production. It’s estimated that Airbus sunk 25 billion Euros into the project, far more than originally estimated, and the aircraft maker never sold enough of them to make a profit. The last Airbus A380 was delivered to Emirates at the end of December 2021, marking the end of the largest passenger plane ever built. Usually, this is not where a plane’s story ends. Old aircraft commonly find themselves flying for smaller carriers or converted into freighters. Unfortunately, the A380 freighter never gained enough customers and wasn’t put into production. And despite the passenger version’s size, it’s so optimized for passengers that it carries less cargo than some smaller planes. As for conversions, the most common explanation right now is that the A380 is too large and too costly to operate as a freighter. So, with a lack of interest from small firms and seemingly not much use in freight, it appears that the A380’s final destination will be the boneyard. Thankfully, we’re at least a decade out before that happens. Some A380s have come back into service during 2022’s spike in air travel demand. And Emirates plans on keeping the type flying into the 2030s. So, you still have time to fly on one, but one day, giants like the A380 and 747 will be a thing of the past. [Ed Note: I’ve flown on three different A380s (1 Air France, 2 Singapore) and they were amazing flights. The planes basically didn’t feel like they were moving. I enjoy Air France, but a Singapore Airlines flight is special and on an A380 it felt like I was a part of the future. The Air France flight was great because it was my daughter’s first trip over the Atlantic:

Somehow, my wife has flown on five different A380s across three airlines (Singapore, Air France, and Emirates)! – MH]

And the author left out how MD’s leadership has destroyed Boeing after being absorbed 😉

That’s a completely different article, but a really interesting one. I’m reading Flying Blind by Peter Robison and would be interested to see a Mercedes post about that.

Assuming 4 people traveling in a car getting 25mpg is about the same.

Fuel cost now…. way higher than staffing costs, but at probably $1k+ per scum class ($2k+ round trip) seat for that 9206 mile (8000 n.m.) trip = a shit ton of daily profits. I bet they would break even with just half of the seats occupied.

Or rather, it seemed that way because it was a Very Large Plane (yup one of these). What an absolute unit.

NOPE. To this day, the A380 that I flew on that was operated by AirFrance was one of the worst (if not THE worst) aircraft that I’ve flown on. (Paris to Johannesburg, SA) This had also been a dream of mine to fly on a A380 / 747 and I was beyond excited when I saw the massive plane amble up to the gate. But AirFrance decided that coach passengers got seats from the 90’s with the hard wired phones in the back, rock hard “cushions”, and almost no recline. I realize that it’s not the A380’s fault, but AirFrance ruined the thing. The aircraft itself was stable and smooth. It moved with purpose and momentum.

Now to find a 747 to compare to…

My worst to this day was a United flight onboard an older 737 with a seat layout that had just 16-inch-wide seats. Then to make my own day worse, I gambled on picking the very last row, thinking that nobody was going to voluntarily sit back there. Sometimes I’m right, and I get the whole row to myself. This time I was VERY wrong, and my seat mates were bigger than me (and I’m not a small person).

Sometimes I can shove myself into the extra inch or so of space created by the interior panel curving towards the window, but the last row on this 737 had the window about a foot ahead of the seats, and thus had a flat panel next to the seats. Blast! I spent the whole four-hour flight contorted. lol

You’d think that Air France in particular would have gone all out to make their A380 experience something extra-special – Airbus is French to the absolute core and those loyalties run deep.

By contrast my two A380 flights (on Emirates and Qantas) have been absolutely superb. Smooth, quiet and comfortable. I remember noticing how thin the seats were – literally half the thickness of any 747, yet so much more comfortable. I guess 25+ years of additional development time will do that…

It was a fusion between Nord Aviation, Sud Aviation, Morane-Saulnier ( SOCATA ) and Potez.

But Nord and Sud Aviation were also merged entities that contained bits of Breguet, bits of Potez, Farman, Nieuport, Blériot, SPAD, Dewoitine, and more.

It’s just a wonder that Aérospatiale worked ( and built the Concorde along with Britsh Aerospace ), and it’s even more a wonder that Airbus ended up working, since it extended that hodge-podge of aircraft builders internationally and get planes built and being hot sales.

You should get your car designer to pretty up the A380 design!!!

There is a way to make use of big airplanes, but there’s not the will to do so: restrict flights into major airports. LHR toyed with this and backed down. All these smaller aircraft flying in at all hours of the day are a greenhouse gas nightmare. So much better to just say “Hey, you want to fly in here from overseas? It must be on a jumbo” and that will reduce emissions, congestion, noise, and all other kinds of problems.

The other options are Avianca with a stop in Colombia in some much newer cabins for a higher price and an occasionally cheaper COPA with a long layover in the worst airport in the Americas.

I wouldn’t mind having to fly with Avianca, but I’d do just about anything to avoid flying with COPA.

Cargo, on the other hand, doesn’t care about connecting flights, which is why I am surprised that Airbus didn’t prioritize the design and marketing of the freighter variant of the A380. Cargo airlines are still operating the 747 freighters even after most passenger airlines have discontinued their service (though their production has also either ended or will be ending soon. Efficiency is the new name of the game; size is no longer the priority.

Wouldn’t be surprised if the idea comes up again as an aftermarket conversion when used A380s get cheap enough for cargo lines to just not care anymore

The 747 was originally designed for freight operations — passenger service was a nice bonus. The top-floor flight deck doesn’t just look cool — it allows for the trick swinging-nose door for easier cargo loading/unloading.

I’m sure the answer to why Airbus didn’t engineer it to be a freighter in the first place comes down to time and money, and it’s always easy to Monday-morning-quarterback it by seeing the bet on passenger service as the wrong one, but it sure seems like a huge market to potentially ignore.

No, the 747 is about the maximum size limit for economical air freight, at least at the densities of current air cargo, and even those frequently ton-out before they volume-out during loading.

The reality is that you don’t really need hub and spoke to fill those larger planes for in demand cities: NYC to LHR – big planes. CVG to say, Berlin? 767 maybe not every day. But I think the airlines want to offer a plethora of flights over anything else, and of course, they are terrified of the off-season. If LHR wants to make these demands, then allow for fewer flights in the off season with the big planes without losing those coveted slots in the summer. Hub and spoke is when you are talking about really small places…. Evansville Indiana to LHR.

The solution to congestion is slot restrictions, which big airports already have. These restrictions limit the number of arrivals and departures and force all airlines operating at a given airport to make the tough decisions on just what is valuable to them — because they can’t add unlimited flights.

Super nerdy thought: Of those routes where it operated profitably, i wonder which holds the record for quickest ROI?