Still, it doesn’t have to be all doom and gloom. New Year, new attempts to improve the quality of our futile existence. David is moving to sunny Los Angeles if his questionable dietary choices (or Torch) don’t kill him first, Mercedes has discovered a new love in the Volkswagen GTI (I’m gonna open a book on how long it is before she buys one) so while you lay on the couch fattened by holiday excess maybe you could take a lesson from these two. Or rather, take a lesson from me, because I am going to teach you how to sketch. Self-improvement is our motto here this week, so wash the turkey grease off your fat fingers and forget whatever misguided car-related projects you had in mind for January. I am going to open you all up to the inner creative side that’s probably been crushed under years of just, you know, trying to survive. Why is sketching so important? It’s how you communicate your ideas to senior designers and modelers. But in the first instance, it’s about getting your ideas down on paper and figuring out what you want your design to be. Think of it as the ‘working out’ part of the process; what do I want my design to look like? The ability to churn out loads of quick sketches either digitally or on paper helps a designer understand what might work and what might not. Designers do their thinking on the page; sketch a front view and you’ve got a starting point for a load more variations, just by tweaking the lines and shapes you’ve already put on paper. You might think you can’t draw. I am here to assure you that you can. You might not be great at it at first, but you can do it. Believe it or not, I don’t just get paid here to write about car design. I get paid to teach it as well. And I have always firmly believed sketching is a teachable skill. So let’s get to it.

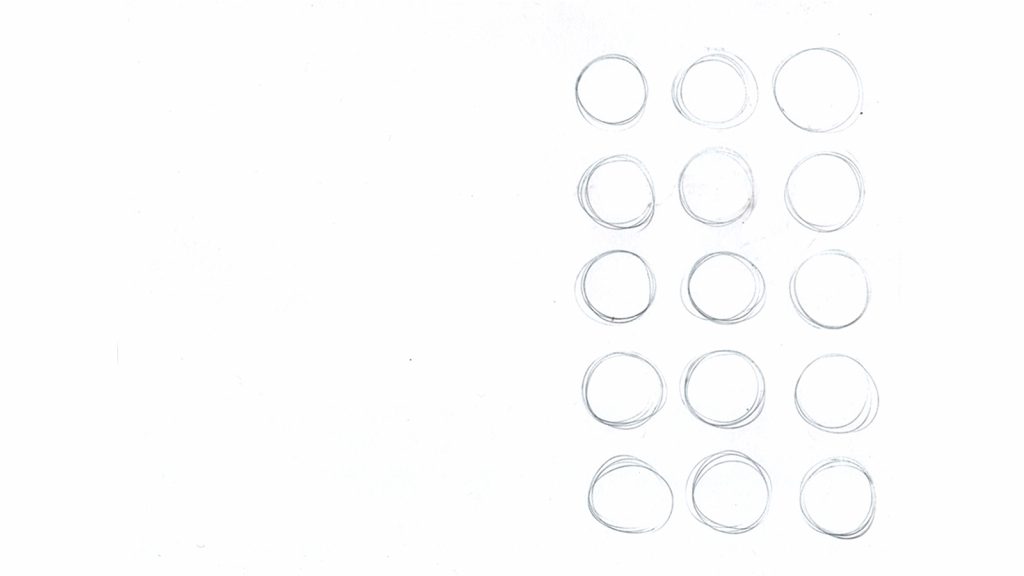

To start with you don’t need any fancy pens, pencils or paper. Whatever you have lying around will do. A lot of student designers (myself included when I was studying) will try different pens according to the linework style of whatever sketch they’ve seen on the internet that week. But nearly everyone, professionals included, circles back to the good old (and design classic) Bic ballpoint. I usually use the fine nib version with the yellow barrel (for reasons I’ll explain in a bit). The clear version is also fine but try to stay away from the broad nib black barreled versions, as they make your linework too heavy. As we’re not going to be using markers yet there’s no need for a marker pad. Just grab some plain white paper out of your printer for now. I usually sketch on A4, but because America doesn’t use THE INTERNATIONAL STANDARD of paper sizes, letter (11”x8.5”) is close enough. Got your pen and paper? Good, let’s go. To start with, we’re going to do some warmup exercises. It’s like doing stretches before going to the gym. These will help “get your eye in.” Without touching the pen on the paper, start by moving your hand round and round in a circular motion. Move your hand from the elbow and shoulder – the wrist and fingers should be rigid. When you’ve got a good consistent circular movement going, gently lower the pen onto the paper, and draw a circle. Repeat this several times, drawing your circles in a line across the page. You should end up with something like this:

Keep going until you nail a reasonably round shape every time. They don’t have to be perfect, but they should be of similar size and repeatable. Once you have circles down, it’s time for some straight lines. Start with your drawing hand nearer your torso and move the pen away from you in a straight line. Your drawing hand will naturally move away at an angle, so rotate your paper to compensate. Draw a line in a single stroke like this:

The trick here is like steering a car or riding a motorbike. Focus your eyes on where you want your hand to go, rather than watching what your hand is doing. Get the lines down quickly as this will help keep them straighter. Again, total accuracy is not the goal; consistency and repeatability are.

Try to keep your line work nice and light. You can always darken a light line, but you can’t lighten a dark one. This is why I usually use the fine nib Bic as if you’re heavy-handed like me (because I’m autistic I also have a condition called Dyspraxia, which affects all sorts of weird things like coordination, fine motor control and language processing). We’ll get onto the importance of line weights in a future lesson, but for now just try to keep a nice light touch of the pen on the paper. So we’ve done our warm-ups, it’s time to actually sketch a vehicle. First up, it’s always important before putting pen to paper to understand in your head what you are going to draw. Is it a sports car, an SUV, or a luxury saloon? Otherwise, you’re just setting yourself up to draw a mess. Because we’re just starting out here, we’re going to keep it simple and sketch something that’s close to all our hearts, a sporty two-door coupe. One of the problems students have is that they are learning to sketch and learning to design at the same time, two different skills. For now, we are just concentrating on the sketching part. Don’t worry about including design ideas in your sketches – for now, we are concentrating on the basics. And the simplest of all is the side view.

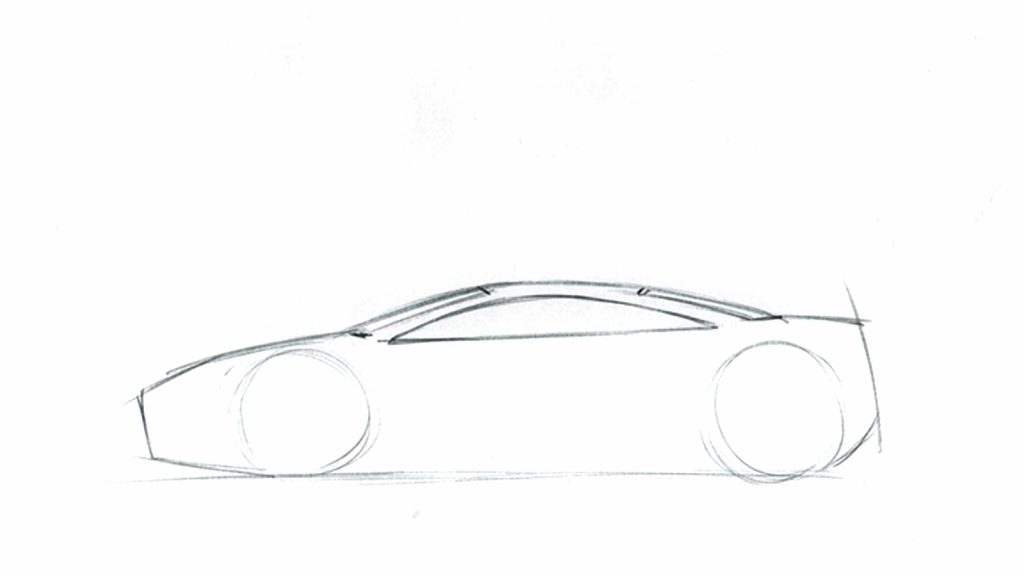

The proportions of all vehicle categories can be ballparked by multiples of wheel diameter. So the first thing to lay down is the wheels. A small-ish sports couple would have a wheelbase of about 2 3/4 to 3 times the wheel size, so sketch two circles about that far apart. It’s okay to use a ruler, a straight edge or if you’re super fancy a circle template to help get this right. When you have your wheels, draw a faint straight line connecting them to represent the ground. Try to cut the very bottom of the wheels off with this line. This will flatten the wheel where it sits on the ground. Next up rough out the roof and general outline. You should be aiming for a nice sweeping curve with its highest point about 1 3/4 wheels from the ground. Our little coupe is going to be FWD, so the A-pillar is going to point past the centerline of the front wheel. The C pillar should land above the center of the rear wheel. Put the lines in very, very lightly until you think you’ve got it right. Once you have that in place, start thinking about the rest of the body work. You want to keep it quite tight to the wheels, and because our car is FWD the front overhang is going to be longer than the rear. You should end up with wheels and an outline profile like this:

Now it’s time for graphical elements, starting with the Daylight Opening, or DLO. The DLO is the glass area between the first and last roof pillars. Although this is a single-point perspective side view, we are going to cheat the sketch a little and show some of the curvature of the front and rear windshield, to give it some depth. Sketch in a DLO, keeping it well within the outline you’ve created. When you’re happy with that, draw in the edges of the front and rear windshield.

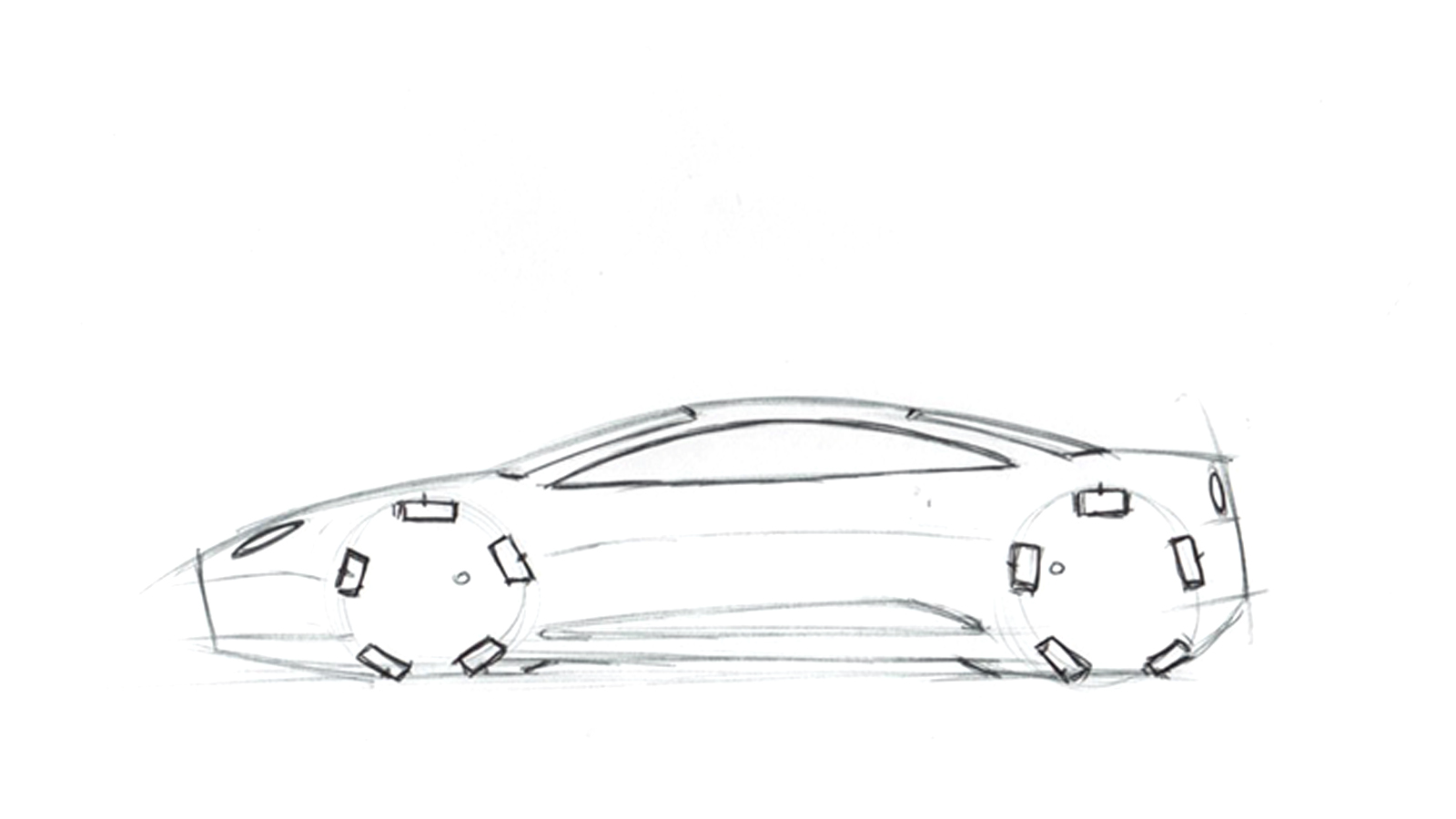

When I used to build 1/24th scale car kits I could never resist gluing and painting the wheels first and offering them up to the body to get an idea of what the finished model would look like. It’s the same with sketches – getting the wheels done helps turn this collection of ballpoint scratches into a car. Start off by indicating the center of the wheels with a little circle to represent the badge, but don’t place them dead center. Instead put them towards the middle of the car, to give the appearance of depth. We’re going to have 5 spoke wheels, so on the very edge of the wheel make a small mark at 12 o’clock, two more on each side just above the center line, and again two more just above where the wheel touches the ground line. This should space all five marks out roughly equally around the circumference. It’s not a perfect method, but for the level that we’re at here, it’s close enough. You can then use these as a guide for a spoke pattern. I suggest drawing a small rectangle around these five marks to represent the holes in the rim.

Let’s add features to the body side. Draw a line running front to rear to describe a feature line. This should angle slightly down toward the front of the car to give it a bit of dynamism. Then to show the shape of the body, draw a curved line connecting the ends of the line between the wheel arches.

Now add in some lights. Press a little harder to emphasize them and then go over the lines of the DLO to pick that out as well. Do the same for the holes in your wheels.

Time for the finishing touches. Tighten up the outline of the car, trying to keep the lines nice and expressive. Then, add a couple more lines at the bottom of the car to indicate the tires on the side we can’t see. Again, this helps the illusion of depth. Finally, add a line to show the curvature of the body and where the highlights will fall. This is going to be about 2/3rds of the way up the body. Hopefully, you should end up with something like this:

If you’re struggling, print these images off and use them as an underlay to sketch over. There is absolutely no shame in this. Professionals do it all the time. Keep it loose, expressive, and emotional. The idea is to have fun here, so if you’re getting frustrated, put the pen down, have a cup of coffee and take a break. I’ve kept this very simple and tried to explain as best I can, but if you’ve got questions I’ll be lurking in the comments as usual. So put some bouncy music on to get you in the mood and get sketching!

Here’s What A Ford Mustang Raptor Would Look Like If Our Professional Designer Had His Druthers

A Professional Car Designer Explains What Makes The Honda e So Wonderful

Here’s What Our Professional Car Designer Has To Say About The New BMW M2

Here’s What A Professional Car Designer Thinks About The Stunning New 2023 Toyota Prius

I have a totally different methodology. I take some graph paper, and draw everything to the real proportions and dimensions the vehicle will actually have. This is how I designed the body for my custom built velomobile, and also some aerodynamic modifications for my Triumph GT6. Then I scan it, and color over it.

Example below:

https://i.imgur.com/oyA6lGH.jpg

Sure, the design is probably not going to impress executives and manipulative marketing scumbags, which is basically what you as a designer are tasked with doing, but it does give a better idea of what the vehicle will actually look like in the real world, which IMO, is what really matters, especially to those who have to engineer it.

You’re designing for yourself, to a very specific brief, and that’s absolutely fine for what you need for your projects. But what your doing in no way relates to how things work ‘in the real world’ or indeed in a real design studio. We’re talking about sketching for ideation, not technical drawings for engineers to work from (which are not done these days as it’s all done in 3D engineering software).

You might not like it, but it’s the way things are done. Designing cars is an emotive and iterative process, and there’s a long way and a lot of stages between expressive thumbnail sketches and finished vehicles.

I think your drawings are awesome. You’re probably my favorite contributor to this site(although Torch would be a close second). I don’t have your talent and found this article informative, because I’d like to try coming up with something without skipping this step just to get some rudimentary grasp regarding how it is done.

And thanks for not holding back your feelings about my comments. People pussyfooting about things and being too scared to say what they really mean is something I find tiresome, but you had the balls to come out and say it. So I upvoted your comment.

Your writing and sketches are one of the things that convinced me to stick around this site. My favorite article thus far of yours is “Our Professional Car Designer Has A Fever Dream And Designs A Jeep Hypercar”. I’d like to one day offer my input as well as get David’s input to revisit the topic of post-apocalyptic transportation in general, not just from the fever dream and comedic perspective, but from a practical perspective regarding what sorts of vehicles would work in that environment and how one could keep them operable with minimal resources available.

As for frank and free debates in the comments section, if I didn’t enjoy them, I wouldn’t participate. This site is much better than that other previous site I used to lurk(but never posted) on.

You’re being unnecessarily defensive about what you do. Your audience IS the executives and marketers, and it looked to me that his disdain was directed there, not at you.

There’s no need to berate someone who gets things done by a different method. We already know that this is your career.

(Note: Many designs that have been done using a form of “trace and improve”, whether with paper or on computer, especially in the hot rod world. You even suggested it yourself as practice in your article above.)

The concept of a car exists and has existed for over a century, and in each era comes with certain templates and expectations that are generally not violated. A perfect example of this is Adrian’s own insistence that huge wheels and ridiculous stance are required in the early design stages. He’s conforming to a current template, meeting a trendy expectation, and interprets that not as a choice but as mandatory for success.

I have tremendous respect for Adrian for making a professional career out of what he does; for convincing people to pay him handsomely for his art. But no matter how much I respect that, I’m not going to pretend it’s the only valid way to do things just because it’s currently the most popular among the professionals.

It reads like gatekeeping to me, as if saying: “You don’t do it the way I say, so your efforts have no value”. The result should be judged. But the process is not exclusive, and should be judged only for its effectiveness and efficiency at getting desired results.

We all want to know how professionals do it because they’re highly effective at getting designs into the market and getting paid for doing so, but that doesn’t invalidate every other creative road. It’s like a chef’s opinion about cooking methods doesn’t make the home cook’s food any less nutritious or delicious.

Gatekeeping is common in almost all fields of work. It’s not exclusive to designers. And it’s part of what allows the paychecks to continue, so it’s not going away. But I prefer to recognize it as part of a larger picture instead of simply accepting it and reinforcing its message.

Hahahahahahahahahahahahahahahahahahahaha beathes hahahahahahahahahahaha.

Adrian is trying to sell his design to those making the decisions on what will ultimately get produced, which is a major component of why his role is important and why he gets paid for it. The way he does things is completely foreign to my own way of thinking, but I don’t run a car company either. Which is why I like his articles, because I learn something new with each entry regarding his methodology and why/how it works, even in cases where I personally still don’t agree with it.

I’ve been doing some sketches of my own based upon the articles Adrian has published. Yes, even with the oversized wheels that I personally loathe. Admittedly, the sketches don’t come anywhere close to his in quality. Adrian could correct me if this is wrong, but I surmise that once the overall concept sketches for a vehicle are approved, it is one of the measuring sticks with which the stylists and engineers use to argue with each other over what decisions are made regarding the car’s construction such as styling cues, trim pieces, cladding, placement of vents/scoops/ducts, wheel/tire size, roofline tapering, wheelbase, front/rear track, ect. I imagine the process of translating a design sketch into something with real-world dimensions is quite arduous and involves lots of design iterations and refinement for a large number of disciplines all coordinated among hundreds of people.

My big question/concern is, how do you make efficiency sell? By “efficiency”, I mean aerodynamic slipperiness with drag coefficients in the low 0.1X range, not the stuff we are currently sold whose average drag coefficient has just barely matched the Rumpler Tropfenwagen of 100 years ago. By “sell”, I mean to sell the car not just to the masses, but the concept of the car to the people making the big decisions on what actually gets produced before anything is even built at all?

My common complaint with cars in general is that they are mostly style over substance, even the most stripped-down basic cars available. And the vast majority of cars have been this way since cars were a marketable commodity. Almost everything sold today is some form of what has been termed on this site as “cybaroque”, the current zeitgeist in the automotive realm. There is no shortage of modern vehicles that have all kinds of fake/non-functional vents/scoops/trim pieces that do nothing but cost the operator money over time by adding drag and padding the purchase price of the vehicle. Not surprisingly, these designs are also divisive, with vehicle enthusiasts that value function over form often finding it to be ugly and over-styled. Yet there are classic cars that are almost universally considered beautiful, because their designs are timeless. Where are the beautiful streamliners of the future we were promised in the middle of the 20th century, the future showcased in cars such as the 1967 Panhard CD Peugeot 66C(drag coefficient of 0.13), 1953 Fiat Turbina(0.14 drag coefficient), or the 1954 Alfa Romeo BAT7(0.19 drag coefficient)?

This sort of aerodynamic efficiency is ultimately what we need in order to reduce the resource footprint and environmental impact of cars, as well as to reduce the cost of making long-range EVs by reducing the required battery pack size for a given range.

Considering that the cars sold today are more aerodynmically slippery than they’ve ever been, in the context of being so uselessly and non-functionally ornate with the cybaroque aesthetic, this is impressive, but there is massive room for improvement by deviating from the fad dujour when university students are getting their comparatively crudely-designed solar cars to have drag coefficient figures in the low 0.1X range.

Stylistically, the new Prius may be showing us the way, in spite of me reading on this site that it is not as aerodynamically efficient as its cybaroque predecessor. As a shape, the new Prius is a good basis to start from, and reminds me of the 1983 GM Aero 2002(0.14 drag coefficient), or the 2000 Dodge Intrepid ESX2(0.19 drag coefficient), among others. The new Prius has the general overall shape of these cars, but through aesthetic choices, manages to look like a totally different car than either of them.

Just because things currently are a certain way, doesn’t mean they need to remain that way. The question is, how do you sell the change? It will take a very talented designer to crack that, and I think Adrian is a designer of that caliber with the potential to do so.

It’s important to not get discouraged and keep plugging away, but it does eventually click and making your hands do what your brain is picturing will come with time.

Drawing crappy cartoons is loads of fun. It can also make money. I made $20 each drawing these posters for a taco truck, with very limited art tools/colors lying around in some warehouse a rave was about to be hosted at, with only about 1 hour to work with in my drunken/otherwise intoxicated state:

https://i.imgur.com/nNyn3hq.jpg

NSFW warning for image below:

https://i.imgur.com/4hJRg6T.jpg

A question for you, Adrian, have you ever tried sketching a sneaker? You’re a designer, so I imagine you have a bit of an eye for all things design. I’m as into Sneakers as I am cars, just curious.

Thanks!

I do have an eye for design and creativity across a lot of different disciplines, something I think is important because a broad outlook and understanding is critical to being a good car designer.

I can’t draw wheels to save my life though, and I’ve never managed to get perspective right.

The most common views used in the studio are front three quarter and rear three quarter, with basically no perspective (these are the views I’ve been using in my renders) .

BTW Adrian thanks for mentioning the autism.I have ADHD and always find it comforting when others talk about such things.It makes me feel less different.

I want to ask- does the autism help you as a designer? I find my brain works brilliantly at choosing what i like (house designs,cars,etc) but really bad at imagining something from scratch. At least it’s something like that.I can easily come up with technical scenarios where autonomous cars would fail,so i guess my imagination works fine in some ways

I didn’t get my diagnosis until I about 39, well into adulthood. I’d known for a long time something was different about me – I was often described as odd or more usually ‘a pain in the ass’. I’m pretty high functioning but where I really struggle is non-verbal communication – reading moods, faces etc and having empathy. The last one I’ve had to work very hard at.

I think it helped when I was studying because it kept me focussed through six years. In the studio it helped me because I was pretty direct and sometimes blunt in meetings (to the point my manager was kicking me under the table!).

Choosing words is my krytonite.Somehow i manage to blunder through but i’m sure many of my posts here are disjointed or incomplete.Apologies to everyone here!

Are you the writer with the cutting sense of humor? I’m pretty sure some of your responses to comments have had me spraying coffee/cake all over the room.Yep pretty sure that’s you 😀

During the pandemic, I took up drawing b/c it was something I always wanted to learn to do and being largely stuck at home, seemed a perfect time to do it. I took a beginner’s course that emphasized the 9 Renaissance techniques for creating the illusion of 3 dimensions – sounds dorky I know but it really worked for me, and I’ve been sketching (badly, but trying) since.

Your motorcycle riding analogy is really helpful for me. I’ve definitely found my drawing turns out worse if I become hyper-focused on “getting it right,” like I’m mentally missing the overall goal if I zero in on one part of things…just like how I’d become target-fixated when I was a beginning rider. Thank you for making that connection explicit!

You can create artwork of real car using a photo as an underlay or reference, but then it’s a drawing (or illustration) as opposed to a sketch. Fitz and Van used to work this way.

BTW sorry to read about Vivienne Westwood’s death…different industry and all, but I have a feeling you might have been a fan.

McQueen was another big loss, and even more tragic. I have a genuine McQueen skull umbrella and it’s one of my most treasured possessions.

I am a bit of a clothes horse and get a lot from fashion, both personally and professionally. Unsurprisingly my current favourites are people like Rick Owens and Ann Demeulemeester.

If you’ll excuse me I’m going to don my high rise Levis and Royal Mail shirt I bought at an automotive parts store for $6.

Awesome tutorial, Mr. Clarke!

https://live.staticflickr.com/8388/28884592295_2d68f34126_c.jpg

https://www.motortrend.com/news/1980-kv-mini-1-design-analysis/

-former itinerant faculty-brat who still treasures the kindness of various professors who would share their enthusiasm about pulp magazines, lens-grinding, the Tulip-bubble, etc with a hyper, annoying little kid